I had hoped to get this post out earlier in the week, but I had so much to say about the first episode of HBO’s new series, The Anarchists, that it took me longer than expected to write it all out. The second episode airs tonight, and I’ll be watching. I plan to share my impressions after each of the six episodes.

This documentary series follows the anarchist movement and community that sprung up around the annual Anarchapulco conference in Acapulco, Mexico. I was at the first conference in 2015, and have attended twice in the years since. I met some of my best friends at these events, and I personally know most of the people who appeared in the first episode. A few of them I would describe as close friends. (I also appear in the first episode, in a blurry, half-second frame. Even if you don’t blink, you’ll still probably miss it.)

These are my people, and this is one of my stomping grounds, both ideologically and geographically. Needless to say, I have big thoughts.

The Anarchists: Episode 1 “The Movement”

I was aware of this documentary as far back as 2018, when some of my friends were being interviewed for it at that year’s Anarchapulco. It was an interesting project, and I figured it would probably be one of those fascinating cult documentary films that never gets much traction in the mainstream. That supposition turned out to be wrong.

When I learned that HBO had picked up the series, I was simultaneously excited and nervous. On the one hand, it’s a major opportunity to present our ideas to the masses, and plus, my friends are in it! (Yay!) But on the other hand, there’s always the potential for messages to be adulterated, for events to be misconstrued, and for all sorts of things to be taken out of context just to make the community look bad in some way. (Yikes!)

But my nervousness dissipated as I reminded myself that there’s no such thing as bad publicity. If the masses see this series and, predictably, 95% of them miss the beauty of the message and decide we are a bunch of crazies, that still leaves 5% who learn something new, keep an open mind about it, and perhaps eventually come around to the ideas of freedom. The fact that many will be demonizing our ideas on the internet is really only a help to the movement. It will get our ideas in front of more eyes. Most of those eyes will be blind, but some will be curious enough to dig deeper, and that’s a good thing.

Overall, I was quite impressed with the first episode. The production quality is excellent, and I loved the little animated segues. It has a logical flow from THE BIG IDEA to different personal experiences of it. The character development is good—although I feel that some of my friends’ quotes and soundbites were chosen for their sensationalism and potential offensiveness, I can’t fault the producers for face-palmy things that actually came out of my friends’ mouths, lol.

Speaking of sensationalism, let’s be clear about the fact that the story we are about to be told through this series is exactly that. It could be no other way, if the producers wanted their film to be aired on a major network. You’ve probably seen the trailer, and the second episode coming out tonight will reveal it anyway, so I’ll go ahead and come out with it: a large part of this series documents a murder that took place in Acapulco, the murder of a member of the anarchist community.

It is a true story, full of tragedy and shocking events, but the fact that these things happened is pretty much unrelated to the ideas we celebrate. In a way, a tragedy is being exploited in order to sell this series. But in another way, the community is exploiting the sensationalism-hunger of viewers in order to get the ideas out.

And so, in order to feed that hunger, in the very first scene we get a big dose of controversiality. There is a book burning. On the beach in Acapulco. With small children present. Shouting things like “Fuck the state!”

I gotta give it to the producers. It’s a hell of a hook. Unfortunately, lots of people watching this will come to errant conclusions for lack of context. Even in the anarchist circles, several of my friends have been uncomfortable with the book burning and the children cursing, calling it “super cringey.”

To me, the burning of the books was not at all cringey, because these are not actual books. They are ripping apart and throwing into the bonfire pages from bound collections of United States regulatory code. I suppose it qualifies as a book inasmuch as it is a sheaf of pages, bound with a cover, but the physical aspects of a book are not the value we uphold when we oppose the burning of books. What we value are the ideas written inside, the creativity of the author, and the principle of free expression that books represent. Reams of regulatory code contain no ideas, no creativity, and no expression whatsoever, and so they are not, in my opinion, to be counted as books.

As far as the children cursing, I get it. It’s going to cause discomfort for a lot of people. If you are one of those people, I invite you to ask yourself why. What is it about these certain words that makes them taboo? Is it a matter of morals, ethics? Does your religious book specifically state that these words are off limits for people under a certain age? Or is it just one of those things that was ingrained in your mind from an early age, that you can’t really think of a valid explanation for?

Personally, I never forbade my child to use curse words, but I asked her not to use them in the presence of other people for whom it may cause discomfort. Not using no-no words is part of being polite and making people feel at ease, even if the custom itself makes no sense. But the kids in this scene are around people who will not feel discomfort hearing those words, so I didn’t have a problem with it.

The Characters

I was delighted to see lots of people I know in the first episode, both as major characters and in brief appearances. As I mentioned, I think the character development so far is pretty solid, but I wanted to give you a more intimate viewpoint into some of the personalities.

Nathan Freeman, the father of two of the cursing children in the first scene and the organizer of Anarchapulco from 2016 through 2018, was a good friend. Sadly, he passed away in 2021. I can see how, from some of his statements in the first episode, he could appear to be somewhat unhinged, but that was not my experience of him at all. Nathan was warm, open, and generous. He was a loving husband and devoted father. It’s true that he had no filter, and would often say things that would sound crazy if you didn’t know him. I would describe him as a big extravert—although he didn’t believe in the extraversion/introversion dichotomy. He was gregarious, fun-loving, and a great connector of people. He was full of ideas and he had the ability to make big ideas come to life. Nathan was a huge supporter of my writing. After reading a chapter excerpted from one of my novels, he loved it so much that he contributed financially for my trip to the Odyssey Writing Workshop, where I spent six weeks learning the foundation of everything I know about story craft. Later on, he connected me with multiple people for creative writing freelance gigs, and he was always asking me about my fiction. I miss him dearly.

Lily Forester, the fugitive from oppressive cannabis laws that threatened to put her in prison for up to twenty years for medicating her chronic pain condition with a plant, is one of the most growth-oriented people I know. I remember meeting her for the first time in person at Anarchapulco in 2017, after having known her online for a year. Back then she came across as a little less sure of herself, a little more anxious and sad. But that was only the top layer. What impressed me about her then, and still does now, was how versatile her interests were and how completely she immersed herself in them, never letting a lack of funds or a language barrier get in her way. At the time she was very into photography and homesteading skills, like gardening and raising chickens. Since then, she has only gotten more awesome. She has developed a steady and powerful self confidence, and she’s an absolute dynamo. Lily loves dogs, cats, and cacti. She knits. She practices aerial circus arts. She knows how to blow glass and ferment things. She is well-versed in anarchist philosophy, is an accomplished writer, and is more committed than almost anyone I know to the agorist lifestyle (basically earning one’s living by transacting on the gray and black markets so as to avoid paying tithes to the murderous state.) When Lily said in the first episode, “We were some of the most anarchist people there,” I thought to myself, “True.” Lily is one of those people whose growth I love watching the unfoldment of. I can’t wait to see what she does next.

Erika Harris is another friend who was featured several times in the first episode. She’s the one who talks about how living in her old life felt like a fraud, and how freeing it felt to be among like minds in Acapulco, prompting her move there. Erika is a beautiful soul: kind, friendly, and vivacious. She’s amazingly courageous. She moved to Acapulco by herself—a country where she didn’t speak the language and had no family or long-term acquaintences—with nothing but a couple of suitcases. I always admired her ability to do that. She is wholly committed to truth and justice, and burns with intensity when speaking on a topic she’s passionate about. She and I have, many times, had fascinating conversations that lasted for hours. She’s an extremely talented writer, and has a brilliant way with words. She opened her home to me in Acapulco, and I’ll always value the time I spent with her there.

Just a bunch of crypto bros?

One of the reviews of the series in the mainstream media calls the Anarchapulco community “crypto bros” and describes the story as an “implosion.” I don’t know about all that. As you can see from the individuals who tell their part of the tale in episode 1, there are a lot of different kinds of people attracted to this philosophy and this community.

You’ve got Jeff Berwick, a financial commentator/party guy. Nathan Freeman, a software developer, and his wife, Lisa, a former teacher. On the outside, the Freemans look pretty much like your typical suburbanites. Then you’ve got John and Lily, two hippie kids who smoke weed and want to farm on terraces in the Acapulco hills. Erika, a refugee from corporate life. She and Luke Stokes, who had a brief appearance at the beginning of the episode, have a very spiritual outlook on life, in contrast to the Freemans’ atheism. Dayna Martin, an artsy, crunchy granola mom who advocates unschooling.

Do all (or most) of these people share an interest in cryptocurrencies? Sure. But are we just a bunch of “crypto bros”? Come on.

One of the things I always love about attending Anarchapulco is the wide variety of people I meet there. From Midwestern grandmas to West Coast hip hop artists to European backpackers, the voluntaryist philosophy attracts all sorts. Rainbow hippies and millionaire investors. Devout Christians and vocal atheists. And yes, also crypto bros, lol. I have had dinner in Acapulco together with a vegan and a carnivore, and we all got along famously. Can any other social milieu offer the same exhilerating diversity, and peace and cooperation among factions? Doubtful.

The philosophy

The episode’s first explanation of the philosophy that brings anarchists together at Anarchapulco is given by Jeff Berwick: from the Greek an (without) and archos (rulers), anarchy simply means “without rulers.”

Then, using a definition provided by a Google search, the documentary further explains the term anarchy as “The organization of society on the basis of voluntary cooperation without political institutions or government.” I think this is a good basic definition of anarchism, and one that most Anarchapulco attendees would agree with. However, it’s important to understand that there are different types of anarchists. It’s quite a contentious subject, actually: who qualifies as “the real anarchists?” Since the etymological meaning is “without rulers”, it really all boils down to how a person defines “ruler.”

For some self-described anarchists, rulers include all types of authorities—like bosses, employers, and religious leaders—and some even conceive of certain societal influences as “ruling” over individuals. So you have anarcho-communists believing that rulers include not just bosses, but capitalism itself; anarcho-primitivists believing that all of modern civilization is a system of slavery; and anarcho-transhumanists who believe that the very state of nature that causes humans to live, die, and suffer through material hardships is an imposed state of rulership. There are many more categories that I won’t go into.

Most of the anarchists who attend Anarchapulco and all of those featured in the first episode fall into the categories of anarcho-capitalist and voluntaryist. These two terms do not mean precisely the same thing, but there is a ton of overlap. People often use the labels interchangeably, and people using either label tend to get along well and agree to a large extent with those using the other.

But beyond that first basic definition of ‘anarchy’, the philosophical thread was lost. I’ll have to vehemently disagree with the makers of the documentary on what it means to be an anarcho-capitalist or a voluntaryist.

This argument that ‘taxation is theft’ is actually the core of this entire freedom movement.

-Todd Schramke (producer of the series), narrating

I honestly can’t imagine any anarcho-capitalist or voluntaryist who has been acquainted with his own philosophy for more than a couple weeks saying this. I suppose it’s possible that Schramke, despite spending six years preparing this work, actually did make the mistake of believing that “Taxation is Theft” is our core tenet, but I don’t think so. I think it’s more likely he described it that way because it’s both more self-explanatory and more sensational than the actual core tenets, which are Self-Ownership and the Non-Aggression Principle.

The principle of Self-Ownership just means that no one has a higher claim to yourself than you do. This principle extends to your body, your time, and your legitimately-obtained property.

The Non-Aggression Principle (or NAP, for short) simply states that it is immoral to initiate aggression (which includes violence and force) against another person. Furthermore, we maintain that this principle holds true whether you are initiating violence all by yourself, or if you band together with others to vote in a “government” that will initiate force and violence on your behalf. Either way it is immoral. However, defensive aggression is morally acceptable under this principle. So if someone else initiates aggression against you, you can use force to defend yourself against the aggressor.

‘Taxation is theft’ is a popular slogan of the ancap and voluntaryist crowd, sure, but this idea flows out of the principles of Self-Ownership and Non-Aggression, and definitely not the other way around.

But of course, TAXATION IS THEFT! is a better catchphrase. It’s controversial, edgy, and better for starting dumpster fire threads on Twitter.

Then the episode delves a bit into a particular thinker to whom it apparently attributes the creation of the philosophy.

And if you want to trace the origins of this philosophy, all roads will lead you back to [Ayn Rand].

-Todd Shramke, narrating

I facepalmed when I heard this line. Just…no. First of all, Ayn Rand was not an anarchist. She did not consider herself an anarchist and no one seriously considers her to be one. Secondly, although many of Rand’s ideas are compatible with the philosophy, she is by no means the sole source of those ideas. There are many roads to this philosophy, and they do not all lead back to her. I won’t pretend that there aren’t some anarchists who came to these ideas by way of the Ayn Rand road, but what about all the other roads? There are the Austrian Economics road, the Lysander Spooner road, the Ron Paul road, the anti-war road, the cannabis freedom road, the unschooling road, the cryptocurrency road, the gun freedom road, and many more.

If you’re not familiar with the ideas behind the philosophy, but you’re curious, watch the short video below. This is an old video, but I still think it’s the best short explanation of the philosophy behind our particular brand of anarchism.

An anarchist paradise?

Everything was just so…anarchist.

-Jeff Berwick

In this clip, Jeff was speaking about his first experiences in Acapulco, before he decided to set up permanent residence there, and quite a while before the Anarchapulco conference was dreamed up. For years, Jeff (and others) continued this characterization of Mexico in general, and Acapulco specifically, as an inherently anarchist place, even after 2016 when the cartel wars broke out.

Personally, I never accepted this bit of narrative. The fact that Mexico does have a government notwithstanding, even the implication that it feels more anarchist never really swayed me. For me, comparing the relative freedom of one country to another is always a very nuanced thing, with so many variables and factors that deciding on a definitive winner and loser is usually impossible, except in extreme cases like comparing North Korea to…well, virtually any other country. One country may be freer in some ways than another country, but incredibly unfree in other ways.

For instance, because of its weaker government, Mexico has more individual economic freedom than many countries. If you want to start a fruit stand or sell tacos on the beach, no one’s going to ask for your license. Similarly, if you want to build an addition to your house, homeschool your kids, keep your bar open all night, raise chickens in your backyard, or any other of the slew of mundane human activities that strong governments seek to regulate, Mexican government does not interfere. In that way, you could say that Mexico is freer than the United States or Canada.

But in other ways, it is far less free. Because, in addition to the levels of government that Americans have to contend with (federal, state, and local), many Mexican communities must grapple with a fourth, and much more in-your-face layer of force: the drug cartels.

These cartels can and do act as a fourth government in the areas in which they hold power. They extort protection fees (taxes) that businesses must pay to keep their doors open. They recruit children and young people into their turf wars (conscription). They execute anyone who threatens their legitimacy as rulers (capital punishment), and often send the dismembered body parts of the victims to their families as a warning. Just like official governments, they promote their own brand of law and order by force and aggression, and sometimes they just slaughter people in the streets for no apparent reason.

Before you object that the cartels running amok is only a result of the relative weakness of Mexico’s government, please watch Larken Rose’s video, linked at the bottom of this post. The cartel situation is because of government, not due to lack of it.

Is Mexico “dangerous”? Well, that largely depends, as it does in most places, on where you are and what you do. No society can ever rule out or eliminate danger, and different places have their own particular dangers to be aware of. I love Mexico, and I have never felt unsafe there. But I know that the dangers exist, and don’t cavalierly pretend that they don’t. Life involves risk, and that is doubly true for the adventurous sort of life I aim to lead. Therefore, for me, the benefits of visiting my beloved Mexico has always outweighed any potential risk presented by the country’s particular dangers.

Nevertheless, the cartels do present an extra layer of force into the lives of many Mexicans, and there’s no guarantee that won’t spill over into an expat community. That many of my fellow anarchist first-worlders didn’t take this truth into account when making their gushing proclamations that Acapulco was “an anarchist paradise” was, as the owner of Verde Vegan states in the episode, extremely naive.

I’m not mad about it, though. Naiveté among visionaries is a forgivable offense. It comes not from any moral shortcoming or lack of intelligence, but often out of an inexhaustible wellspring of hope and good will, and the deeply rooted belief in human potential. We all have our blind spots. Hopefully, as we continue integrate the ideology into our understanding, and as the community around it matures, our tendency toward such naive assessments will subside in equal measure.

The maturation of the movement

A common sentiment among the interviewees was that they were running toward greater freedom in Mexico, and away from a stifling, unfree life in their country of origin. There was a time when I shared this desire. I never thought Mexico was “it,” but I was somewhat obsessed with the idea of finding or building the place where we could create our principles-first society.

How can you live your life more free? How can you live your life away from the state?

-Nathan Freeman

We were trying to push toward that goal of a pure anarchist life.

-Lisa Freeman

We could just ride out the apocalypse here.

-Lily Forester

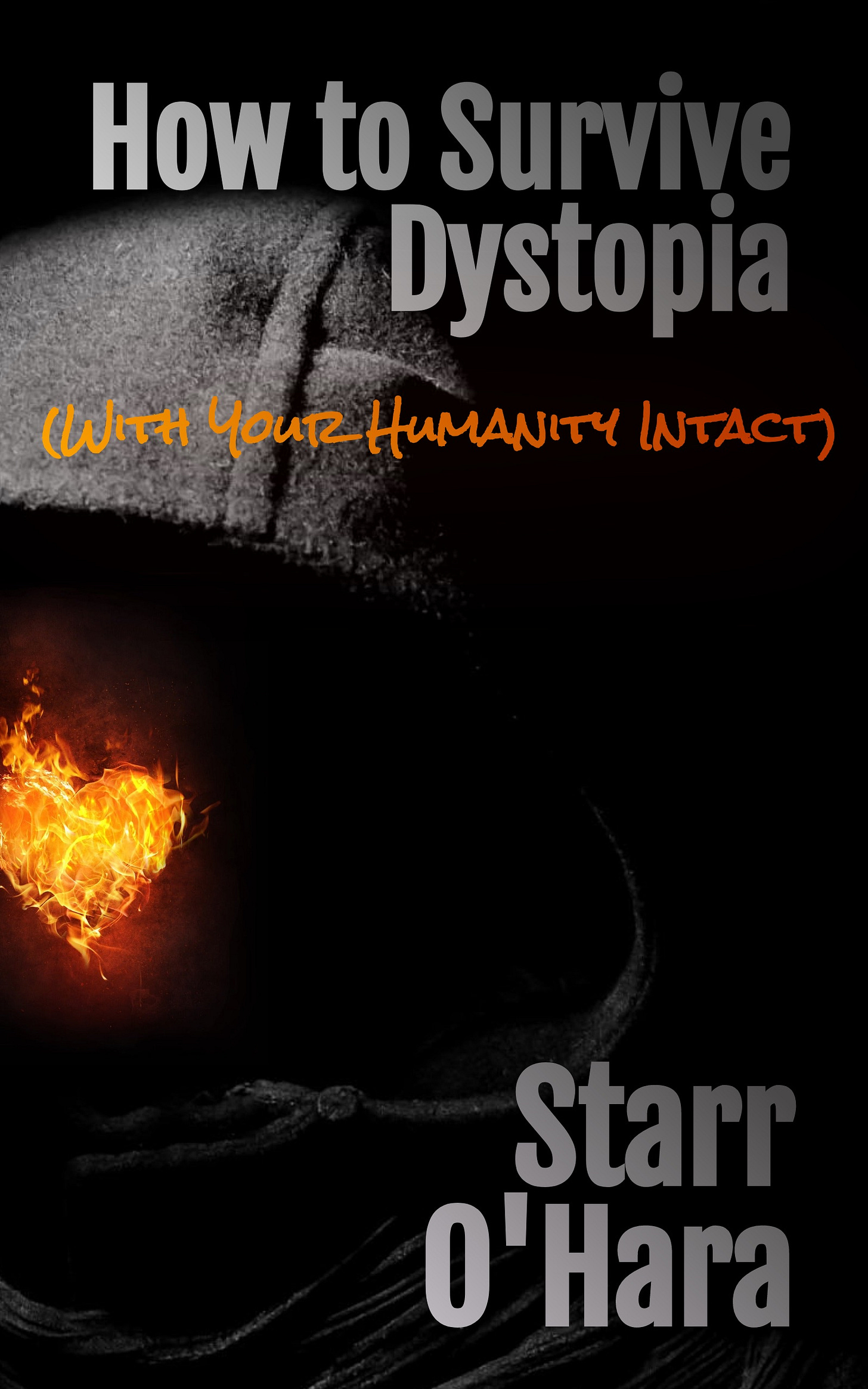

It’s my hope that as our movement matures, we’ll stop subscribing to the dualistic notion that “here is tyranny” and “over there is freedom.” Over the past couple of years—as an unarguably tyrannical agenda wrapped its tentacles around the whole world, leaving practically no place untouched—I and many of my anarchist friends have begun to understand that freedom is within, and that it’s not necessarily where you live, but how you integrate and express that inner freedom that counts. I’m still mining that concept for greater truth, but I wrote a bit about it in my new book, How to Survive Dystopia (With Your Humanity Intact).

So, while an “anarchist paradise” somewhere away from the prying violence of the state would be nice, I no longer yearn for it. In order to advance the ideas of freedom, in order to really weave them into the human experience, we’re going to need to be everywhere. Small communities, expressing as much freedom as is possible in spite of the outer statist reality, that’s the key. And expressing not only freedom, but deepening and strengthening our integration of other indispensable virtues as well. Virtues like self-responsibility, compassion, honesty, and diligence. We need to objectively acknowledge the unfreedom around us, that sometimes impinges on us, but we must never let that stop us from exercising freedom and its corresponding virtues to the fullest extent possible. We could form a chain of tiny beacons to light the way for others, once they’ve had enough of the state’s madness. That is my hope for the movement.

My cameos

I appear twice in the first episode. Well, sort of.

Links to other people’s thoughts on the episode:

Lily Forester (who is heavily featured in the first episode) shares her thoughts on her blog, Highly Functional Growth.

Larken Rose (also featured in the first episode) gives a video response to mainstream media’s demonization of the philosophy and the movement followed by the series. It’s a great video. I highly recommend watching it.

Karen Keener (a fellow anarchist and VIP member of my Extremists Being Awesome productivity group, shared her impressions on The Sovereign Mom Substack.

Thank you for reading!

If you love this essay, please share it. If you’d like more essays (and fiction!) in your inbox, subscribe for free! And if you’d like to support this newsletter and my other projects, please consider the options below.

-Starr

Get the Book

My new book, How to Survive Dystopia (With Your Humanity Intact) is available in paperback and on virtually all digital platforms. Find your preferred format:

Social Links

Follow me on Twitter

Connect with me on MeWe

Follow me on TikTok

I'm honored at my mention.

As I don't have TV service I will have to live vicariously through your descriptions :D